第二十九章

27 August 2075

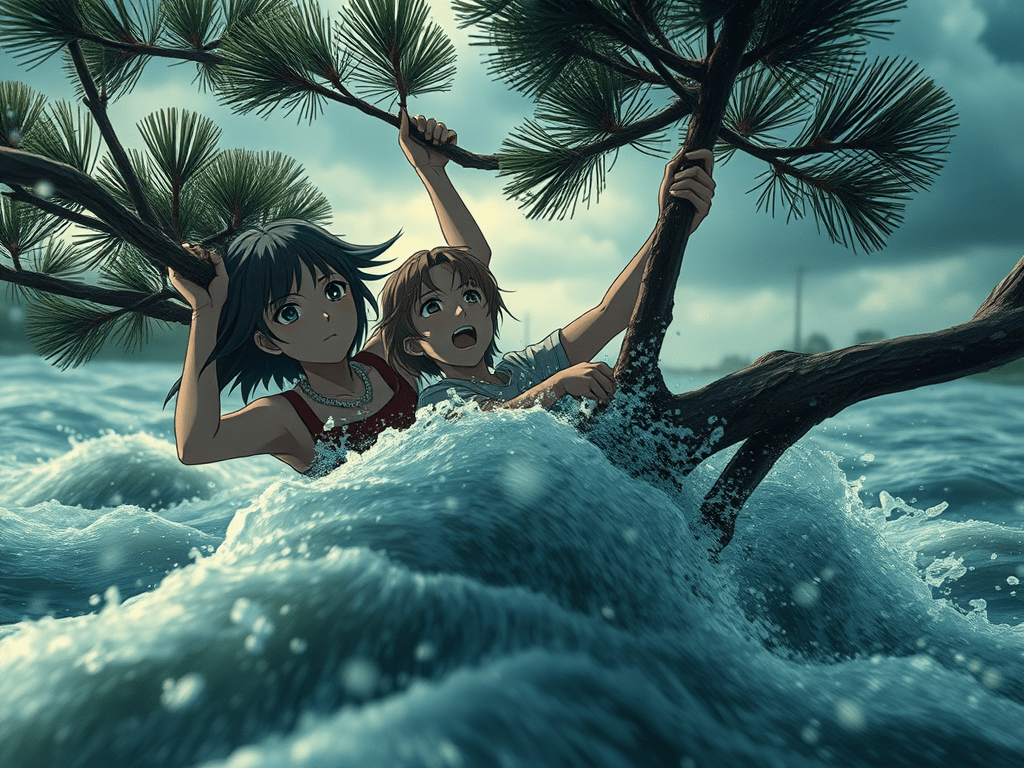

Shoichi could feel the sadness, the torment, the distress rising inside him. Was this the same emotion that Kimiko was feeling? Aoyagi-sensei’s questions had caught him by surprise and he did not have the space to mentally prepare himself for talking about that time in March 2011. So many years ago, but the memories were still raw, still plunging through his heart like the cold of a winter’s morning.

Shoichi felt himself losing control, emotions came rushing up from his stomach and he let out a long pain-filled cry. He needed to remember a place, a time when he felt peace, when he had begun to grieve and finally accept his loss.

***

Shortly after they had moved to Mito, Shoichi and Kimiko decided to travel further south to a place called Kashima to visit the famous Kashima Jingū, a shrine dedicated to Takemikazuchi no Ōkami one of the patron deities of martial arts.Rather than drive, they decided to take the train from Mito and arrived at Kashima station on a two-carriage express. It was November and although not quite winter, the air was already crisp and cold, the sky a washed out blue without a cloud in sight. Although he had read about the shrine before and vaguely recalled studying about it at school, Shoichi was more au fait with the local football team, the Kashima Antlers, as he often watched them play in matches on the television.

For such a famous place, the station was small and understated; just two lines, one north to Mito and another south-west into Tokyo. The concrete stairs descended to the exit barrier and out onto an open concourse paved with red bricks over which were laid strips of dimpled grey rubber matting that acted as a guide for those with sight disabilities. In front of them and to their left was a semi-circular turning area to allow cars to get closer to the station from the main road. There were also three bus shelters; two for local bus services and one for coaches taking passengers into Tokyo along the express toll-roads. Other amenities around the station included a three-storey block of flats, a high rise business hotel, an English language school, a hair salon and the ubiquitous pachinko parlour, this one simple called “M”. Further in the distance, beyond this instantly forgettable representation of modern Japan, stood the thick ancient forest of sugi Japanese cedar trees that surrounded Kashima Shrine.

Rather than walk south to enter the shrine through the main torii gate entrance, Kimiko and Shoichi headed east along a road that would take them first to the lower part of the shrine.

‘It doesn’t feel as holy here as I expected it would,’ Shoichi said, unable to hide the disappointment in his voice.

‘Give it a chance, Shoichi,’ Kimiko said. ‘The shrine was here long before the station and that collection of buildings around it. You can’t expect the whole city to have a spiritual feel. This isn’t like Nikkō or Kamakura.’

‘Yes, I suppose your right,’ he said. ‘I just hope that this doesn’t turn out to be something of an anti-climax.’

They continued along the road, which was smooth with freshly laid tarmac. Shoichi wondered when it had been re-surfaced as the markings were a sharp white. The area into which they walked was mainly residential, a mixture of modern and traditional houses, butting right up to the roadside. After a few minutes and to their right was the very edge of the Kashima Jingū forest which looked like it wanted to spread out even further if it wasn’t for the road stopping its progress. Although many of the trees had lost their leaves for winter, the evergreen pines and Japanese cedars provided enough foliage to continue to give the forest its density and impact.

On the left of the road, sandwiched in between two blocks of low rise flats, was a boxing gym which Shoichi found strange as he was expecting more martial art dojo to be established in the city, considering the shrine’s heritage. Boxing seemed out of place, although judging by the smart looking building and full car park, it had found its niche.

The road then doglegged left and then right again, the line of buildings opened up a little affording them a view of the concrete construction that contained the train track that they had come into Kashima on; suspended in the air rather like a Roman aqueduct, they had enjoyed the views over plots of farmland left fallow before the next crop of rice would be grown from late spring of the following year.

‘It all feels rather run down, don’t you think?’ Shoichi said.

‘Yes, I know what you mean,’ Kimiko agreed. ‘I was always under the impression that Kashima had plenty of money coming into the city from all the activity at Kashima Port. It’s a much bigger operation than Ōfunato and, in fact, I read somewhere one of the biggest ports in Japan.’

Actually, I used to work with a guy who came from Kashima and he told me that the peak of activity for the city was in 2002 when it was one of the host cities for the football World Cup,’ Shoichi said. ‘He told me about how much investment the tournament brought into the area with new roads and other infrastructure. Since then, however, the money has moved further south into a city called Kamisu, I think most of the Kashima port sits in its border, and he spoke regretfully and almost bitterly about how Kamisu, then a town, grew in size and then merged with a neighbouring town to become a city. Since then, it has overtaken Kashima in population and economic output.’

‘Wow, you seem to know quite a lot, Shoichi,’ Kimiko said, half mockingly, half impressed.

‘Do you know, I’d completely forgotten that conversation until now,’ Shoichi said. ‘Funny how the mind works, isn’t it?’

They eventually, after about twenty minutes in total, reached the end of the road as indicated by a change from tarmac to stone paving slabs with four short but thick concrete bollards in place to stop vehicles from inadvertently entering the shrine’s grounds. To the right was a gravel car park that was less than a third full and a toilet block.

‘Do you need to go?’ Kimiko asked, her head inclined towards the wooden building.

‘Yes, I think I do actually,’ Shoichi said. ‘Thank you for reminding me.’

Kimiko walked a little further along the stone paving to find somewhere to stand and wait for Shoichi. She saw ahead of her on either side of the pathway, two piles of earth, each encircled at the base by large smooth stones and squared by four wooden posts through which some rope had been threaded creating an enclosed barrier. From the rope hung shide paper streamers folded so they zig-zagged, looking like forks of lightening. By one of these constructions was a plaque onto which the following words were written.

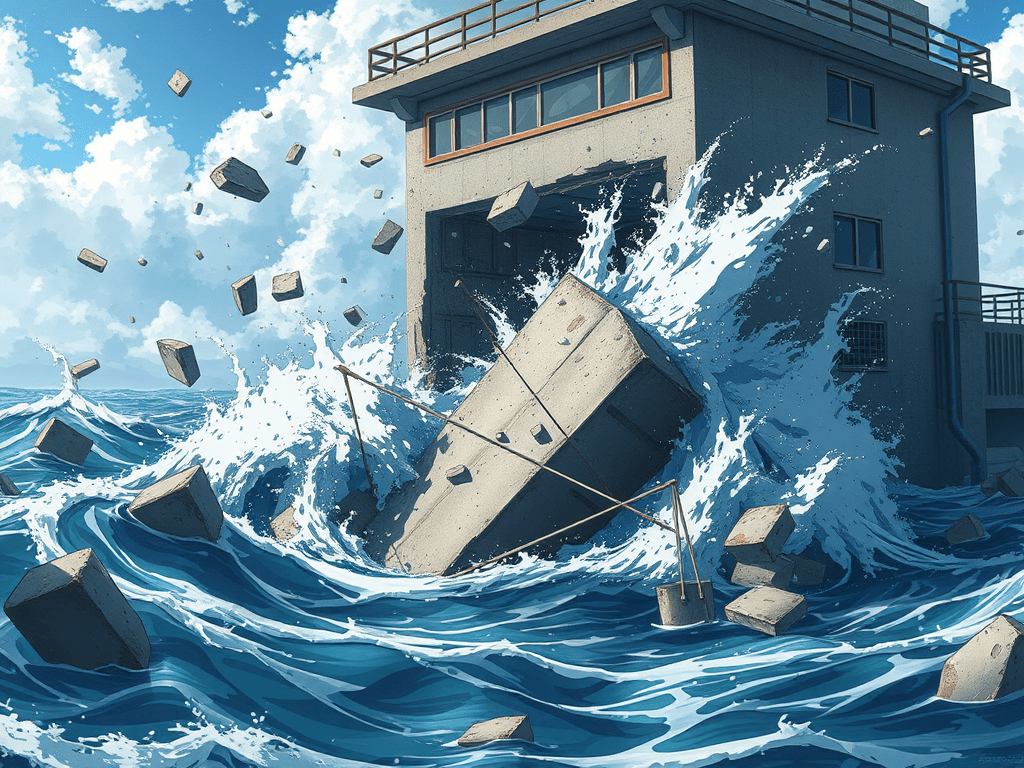

23rd Heisei Year 3rd Month 11th Day

On this day, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck, destroying the shrine gate that once stood here. The Kashima Jingū Shinto Authority has decided not to reconstruct this shrine gate, instead leaving the base blessed but untouched in recognition of the power of nature and in remembrance of those who lost their lives.

Shoichi saw Kimiko standing by the plaque and walked up behind her to read the words that Kimiko had now read through three times. It was a sobering moment for them both and Shoichi put an arm around Kimiko as they stood there in silence. There was no doubt that they were thinking about their respective and joint lost loved ones. Kimiko turned to him.

‘I still miss them every day, Shoichi,’ she said. ‘I get so angry thinking about why they had to be taken away from me, taken away from us.’

‘I know,’ was all that Shoichi could manage in reply but this was not empty empathy, he really did know exactly how Kimiko felt.

From a raised and covered platform, close to where they stood, the sad and hollow sound of an ocarina floated across to them, not cutting through but soothing the silence. The man who came here once a week to practice would not know the significance of his choice of song but as “Yesterday” drifted through the air, Shoichi and Kimiko moved towards where he played and sat down on a wooden bench near a pond that was filled with water that flowed gently over rocks placed deliberately to create a miniature waterfall. The ocarina player was used to people stopping and listening to his songs but the couple in front of him sat through the whole of his practice session that lasted the usual half an hour. As he put his instrument away in its padded leather-bound case, the couple bowed towards him and said ‘Thank you.’ Not knowing how to react, he simply bowed back and went on his way.

Shoichi and Kimiko got up from the bench and walked towards the pathway that led steeply up and further into the centre of the forest towards the main shrine. Before they reached the path, they walked past a larger square pond that contained koi carp and the supporting posts for a tree that had grown horizontally out of the bank.

‘That’s quite incredible,’ Shoichi said. ‘Look at where that tree goes into the hillside, its roots have spread out just as if it were growing conventionally.’

‘It certainly is something that I’ve never seen before,’ Kimiko said. ‘And how unusual that it remained standing when the earthquake caused so many other parts of the shrine to fall down.’

‘The miracles of nature,’ Shoichi said in response, looking at the tree which at some stage in its long life had finally decided to grow towards the heavens so that above the pond it bent suddenly and at ninety degrees to the rest of the trunk.

And it was a miracle, hundreds of years old, growing at an impossible angle but the tree survived and would continue to survive, probably for hundreds of years more. In the spirit of the Shinto religion, it had been recognised as a deity with a rope tied around its base and adorned with shide like they had seen at the entrance.

Once at the top of the steps that they had climbed to get to the level of the main shrine, Shoichi and Kimiko found themselves in dense forest that blocked out much of the light until they reached a wide and straight sandy path. Bordering this path were fine examples of Japanese cedar trees that were immense in scale. With a circumference of around six metres and up to forty metres tall, these were giants that served to make the visitors to the shrine fully appreciate the nature around them. What struck Shoichi was the tranquillity; the only sound he could hear was the occasional call of a pheasant. For everyone else, they walked in silence. His doubts about the holiness of Kashima Jingū were now banished from his mind and he felt like he had done at the top of Fuji-san, completely in awe of nature, of life, and a sense of calm overcame him. One look at Kimiko told him that she was feeling the same.

To the left of this main path was a smaller and narrower trail that led deeper into the forest towards a historically significant and, for Kimiko and Shoichi, poignant area of the shrine. With its own torii gate but with a surprising lack of any other border or fencing, was the kanameishi key stone which legend told held in place the Ōnamazu giant catfish. This stone was watched over by Takemikazuchi no Ōkami, the God to whom the shrine was dedicated but on the occasion when the deity’s concentration lapsed or when away from the shrine in October – the Godless month – the catfish was able to shake itself lose and the thrashing of its tail was said to cause earthquakes across Japan.

‘The stone is so small,’ Shoichi said, slightly puzzled by the keystone that was no larger than a dinner plate in diameter and that rose out of the ground by about ten centimetres. ‘I don’t think that I’ve ever seen any pictures of this before, or at least not ones that I can remember, but I expected to see something more like a boulder than a stepping stone.’

‘Don’t you remember from school, Shoichi?’ Kimiko asked. ‘This is just the tip of the stone and underground the rest of it lies hidden from view. The Mito Shogun dug around the stone for three days to try to uncover its base but even in such a time was unable to dig deep enough.’

‘No, I don’t remember,’ Shoichi replied. ‘Although I expect it would have to be a pretty big stone to keep Ōnamazu in check.’

Shoichi was unable to suppress his feeling of anger towards Takemikazuchi whom he wished had taken more care to keep Ōnamazu under control in 2011. Nevertheless, the story evoked in him a huge sense of respect for the power of nature and the devastation that natural disasters – not just earthquakes but typhoons every autumn and landslides that had become a problem in recent times – brought to Japan each year. It did feel like a trade-off offered by the kami-sama; in return for scenery so beautiful that it was the envy of the world, Japan had to accept the vulnerable position that it found itself in, situated on an active fault line at the edge of the Pacific plate.

As they did at the top of Fuji-san, Shoichi and Kimiko prayed, throwing money onto the stone as an offering to Takemikazuchi for continued guardianship of the keystone and to Ōnamazu to prevent an earthquake like the one in 2011 from happening again for a very, very long time.

However, it was the gigantic trees that Shoichi pictured in his mind as he sat at the hospital, and sure enough, as if he were actually there, a peace descended over him, massaging his emotions, removing the pain and dampening the fear of further loss; his spirit relaxed.