第二十二章

11 March 2011 15:10

There was no doubt about it, Hiroshi was dead.

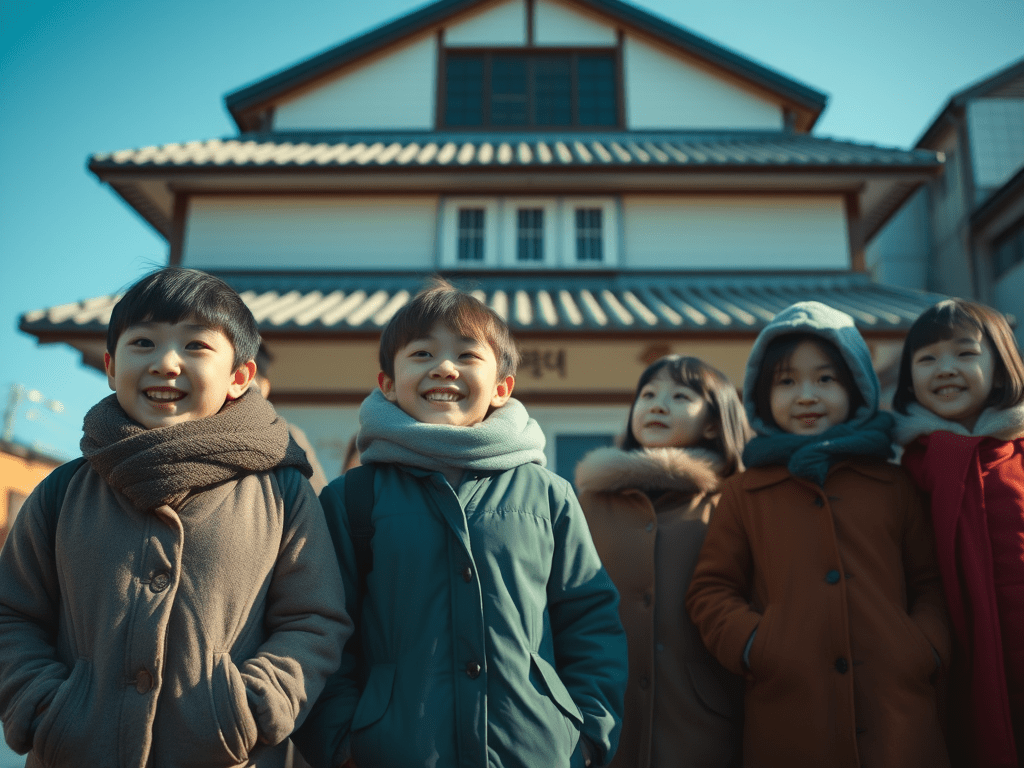

Kinoshita-sensei snapped to his senses on hearing the tsunami warning, lifted Hiroshi’s body onto his right shoulder and walked towards us, his face damp with tears. As more of the students realised what had happened to one of their classmates, a sense of hysteria set in.

‘We have to get to higher ground!’ Ohara-san shouted. ‘If a tsunami is on its way, we can’t stay here. We’ve got to get back to the port office. We’ll be safe there.’

‘Hurry, hurry!’ shouted Kyōto-sensei sweeping his right arm through the air to encourage movement. He realised the extreme danger of the situation; by the time the warnings are heard it can be just a matter of minutes before any potential tsunami arrives.

We began to move away from the open port area walking at a brisk pace but not in fear for our lives as we felt that the worst was behind us. Surely nothing more would happen now that the earthquake had passed? The first aftershock hit, nothing like the intensity of the main quake, but enough to cause more buildings to shake and completely freak out the class.

‘It’s happening again!’ screamed Asuka. ‘Quick, we’ve got to get out of here!’

The class broke into a run and I joined them. Kyōto-sensei and Ohara-san ran alongside us to try to get us to calm down. They knew that without order we would be running off in different directions making it much more difficult for them to keep us safe. Kinoshita-sensei continued walking as he was carrying Hiroshi and so couldn’t keep up with the pace of the others.

‘Everyone stop running!’ Kyōto-sensei shouted at the top of his voice as students continued to disperse. ‘Now!’

‘Listen to your teacher, children,’ Ohara-san added. ‘Follow me and I will get you somewhere you can be safe.’

Tsunami has been confirmed moving towards the port.

Please move to higher ground immediately.

Tsunami has been confirmed moving towards the port.

Please move to higher ground immediately.

It was the announcement that we needed to hear to get us to focus and we gathered back together to head towards the port office as Ohara-san had suggested we should. I looked behind me and up Ōfunato Bay but could not see anything different to when we had been stood there before the earthquake had struck, waiting for the Hakudo Maru to come into port.

I was a little reluctant to enter the building as another aftershock occurred just before we arrived and I thought that surely we would be better off in a wide open space rather than three floors up in this rather old and shabby looking office block. After we climbed up the internal concrete staircase, Ohara-san ushered us through to a large meeting room on the third floor that ran across the back of the building and afforded a view of the port that on another occasion would have been quite spectacular. Large sliding glass doors formed this back wall and there was a wide and deep balcony that quickly filled with students from 4-A, who were anxious to get outside and take in the effects of what they had just been through.

From up here I could see Kinoshita-sensei who was now struggling to support the weight of Hiroshi whom he had carried all this way from the place where he had hit his head and died.

‘Hurry up, Kinoshita-sensei!’ Takumi shouted. ‘Please get to safety!’

Once these words had left his mouth, other students joined in until almost all of us were shouting words of encouragement to Kinoshita-sensei to give him the strength to reach the port office and the balcony where we stood. We then saw Kyōto-sensei rushing towards the two of them to help Hiroshi’s body down from Kinoshita-sensei’s shoulder. Between them, they were able to better support his weight – Kyōto-sensei with his forearms under Hiroshi’s armpits, locking his hand together with fingers interlaced and Kinoshita-sensei holding onto Hiroshi’s legs – so the two of them could make faster progress getting out of the danger zone.

Behind me, Ohara-san was talking hurriedly with two of his colleagues who were getting a television turned on and tuned into the NHK news to watch as events unfolded. A few of us, including me, gathered around.

The newsreader announced that the epicentre of the earthquake was in the Pacific Ocean, at the same latitude as Sendai city. All down the east coast of Japan, the intensity of the earthquake had been measured to be at least a shindo scale of five plus. Where we were in Ōfunato, the strength was measured as six minus, just two levels down from the maximum rating of seven. This was the biggest earthquake I had ever experienced in my life and now that I knew the strength was surprised that more buildings had not fallen down. Okāsan had told me about the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake in 1995 which caused untold damage to buildings, roads and quays around Kōbe in west Japan. It had led to changes in the rules about how new buildings were designed and built to withstand earthquakes and from the comparative small scale of damage around the port, Japan had learned something of a lesson from the last time an earthquake of this size hit the country.

The newsreader then announced that they were going to join a reporter who was in a helicopter hovering over the Pacific tracking the tsunami that was heading towards the coast.

I am just off the coast of Natori in Miyagi Prefecture just south of Sendai. The earthquake which has shaken much of the east of Japan happened at fourteen-forty-six and there is a tsunami warning in place. If you have not done so already, please move to higher ground as a matter of urgency.

The camera panned around to the left and further out to sea. The reporter could barely contain himself.

It’s a tsunami! The tsunami is coming! Waaagh, look at the size of it! It’s got spray coming off the top of the leading wave and stretches out as far as I can see. This is so dangerous!

As I stared at the screen, the camera remained steady as the tsunami moved determinedly towards the Natori coast. But it was not just the one wave.

Look, there is more than one tsunami! Two, three, four, five waves are rolling in behind the first. They just keep on coming! The leading wave is approaching the coast now…I can’t believe it, the sea has crashed over the beach and up onto the land behind it. Taihen da!

It was like something out of a disaster film. The wave was just eating up the ground, travelling over rice fields and through buildings as if they were not there. I had never seen anything like this and hoped that the people of Natori had listened to the warnings and evacuated their coastal homes. The scenes on the television were interrupted by a member of Ohara-san’s team shouting from the balcony.

Tsunami kita zo! ‘The tsunami’s arrived!’ he shouted. ‘I can see it entering the port. Turn on the sirens!’

As the instructions made their way through the meeting room and to the control centre across the corridor, a deafening sound filled my ears much like an air raid siren that I had heard when watching old news clips about the war. Rather than wanting to hide, I was desperate to see the tsunami as it came into the bay, a part of me wanted to face the threat that we had just been fleeing from. Other students were pressed towards the front of the balcony both frightened but drawn towards this natural phenomenon.

‘I can see it!’ shouted Yuka pointing out towards the Osaki Cape from where we had earlier that afternoon seen the Hakudo Maru entering the port.

At first, I couldn’t see anything but then when I focussed on the level of the sea, there was a strip of water that had risen above the rest, less like a wave that breaks onto the beach and more like the beginnings of a wave out in the middle of the ocean.

‘It’s moving so quickly!’ Rikimaru exclaimed. ‘It’s going to reach the port very soon.’

Within a few seconds, the water pushed into the bay and, like the wave on the television at Natori, just kept on moving north and spreading out through the gaps between the warehouses and other buildings in the lower port, flowing into the concrete factory on the far side of the water. In a matter of minutes, the whole area was flooded.

‘Don’t worry children,’ Ohara-san reassured us. ‘This is a big tsunami but we’ll be safe. I think that the worst is over now.’

As I looked out across the bay, the ocean just kept on rolling in. As the port literally filled up, water levels at the side started to rise and eventually breached more of the port walls, like an overflowing bath, to cover the flat area where we were stood less than twenty minutes ago. As it spread towards us, some of my classmates started to panic.

‘It’s moving this way!’ Natsumi shouted. ‘The water is coming to get us!’

Kyōto-sensei moved towards Natsumi and gently led her away from the group of us on the balcony, sensing that her panic could be contagious.

‘We’re going to drown!’ she continued, becoming increasingly out of control. ‘Get out of this building and run for your lives!’

I did not think that anyone would listen to her but Hiroki, who had given me a big bowl of rice that lunchtime, dashed out of the room and down the stairs.

‘Come back!’ Kinoshita-sensei shouted as he ran after him. ‘It’s not safe out there. Come back Hiroki!’

Through his panic, Hiroki must have got confused as instead of running further away from the wave, he ended up running towards one of the warehouses that we had passed on our way to this building. We could see him from our position on the balcony.

‘Hiroki!’ I shouted. ‘Get back up here. It’s not safe down there. The water is coming!’

These were not just words to get him to listen. The sea kept on moving and was now spreading quickly westwards towards us and towards Hiroki.

‘Hiroki!’ Haruka joined in. ‘It’s too dangerous down there!’

He was still panicking and rushed into a nearby building only to appear again a few moments later. In the same short time, the waters had arrived at the bottom of the building where we were sheltering, lapping up against the outside walls. Although initially only ankle-deep, the water rose quickly causing him to lose his footing. I saw Hiroki get flipped onto his back and carried away like a plastic boat at the beach. The water was now flowing freely three floors below where we stood and I watched on, completely helpless to do anything.

***

As Shoichi began to regain consciousness, he could hear the conversations between students getting increasingly louder before his brain re-engaged; he realised where he was and slowly opened his eyes. Standing over him were Yoshida-sensei and Onuma-sensei, the school nurse, who spoke first.

‘Are you alright?’ she asked. ‘You fainted a moment ago. Does anywhere hurt?’

Shoichi moved cautiously at first, feeling drowsy from the short but intense period he was out for, but did not feel any pain and guessed that he must have landed reasonably softly.

‘Don’t get up just yet,’ Onuma-sensei said, laying a palm gently on his chest. ‘Just stay there on the floor for a bit longer while the blood flows back to your brain.’

He took her advice, and lay next to the plate of first base, staring up at the leaden sky wondering what had just happened. As he gathered his thoughts, he remembered what had preceded this incident and memories of the earthquake crashed over him all of a sudden causing Shoichi to sit up abruptly and call out.

‘What’s happened to class 4-A?’ he asked. ‘Have you heard any news? My little sister is in that class. Does anyone know if she is safe?’

Shoichi began to panic and with it his breathing got shallower and more rapid until he was hyperventilating and in danger of losing consciousness again.

‘Just slow down your breathing, Shoichi,’ Onuma-sensei said, trying to keep him calm. ‘Nice deep breaths now. In and out. In and out.’

Shoichi did as he was told and continued breathing this way until he regained some control. Nevertheless, he still felt slightly nauseous and light headed so did not make any sudden movements.

‘We haven’t heard anything from Kinoshita-sensei,’ Yoshida-sensei said. ‘However, I’m sure that he and the children are all safe. Don’t forget that they had Kyōto-sensei with them as well.’

‘But I need to know that Haruka is OK,’ Shoichi said raising his voice, causing other students to turn around and see what the commotion was all about. ‘Has anyone tried calling Kinoshita-sensei?’

‘Unfortunately, all of the mobile signals have been disabled to allow for emergency services’ use only,’ Yoshida-sensei continued. ‘We’ve tried Kinoshita-sensei’s mobile phone a couple of times but are unable to connect.’

‘But I have to find her!’ Shoichi said. ‘I need to know that she is still alive!’

‘It’s too dangerous, Shoichi, you must stay here,’ Yoshida-sensei said firmly. ‘We have a message out on local radio asking parents who are safe to come to the school to collect their children. It’s absolutely out of the question you leaving without your parents or another adult relative.’

‘I must find Haruka, though. She could be in danger,’ Shoichi said, his brotherly instincts driving his thoughts.

‘And you will be putting yourself in danger by going out of the school grounds. Many of the buildings around here have been damaged and could fall down at any moment,’ Yoshida-sensei said. ‘There’s also the risk of a tsunami, Shoichi, so nobody should be getting any closer to the water.’

Shoichi knew that it was dangerous and he was not even sure what help he might be able to give if he did head down to the port. However, he also knew that he would never be able to forgive himself if he did nothing and later found out that Haruka was badly injured or, unthinkably, something even worse. Slowly, he got to his feet and began walking around the grounds for a short while, all the time being watched by the teacher and school nurse who moments before had witnessed his collapse. As the minutes went by, Shoichi felt more in control of his body, the sickness subsided and, sensing his recovery, Yoshida-sensei and Onuma-sensei suggested that he return to where the rest of his class had congregated, allowing them to resume their other duties.

Ordinarily, the teachers at the school would have made sure that the students under their care remained in the school grounds until collected by an adult, but on this occasion many were distracted by thoughts of their own loved ones with whom they had yet to make contact following the huge earthquake of twenty minutes ago.

Someone should have seen Shoichi casually walk past his classmates and tag onto a smaller group walking towards their parents who had come straight to the school from their homes or workplaces and were now standing at the school gate, but Shoichi blended in, unnoticed.

On a normal day, one of the adults at the school gates would have noticed that Shoichi walked past them and out onto the road that headed down to the port, but they too were distracted and overcome with emotion knowing that their own children had not come to any harm.

Shoichi continued to walk at a casual pace for as long as he felt he could without raising suspicion but, like a racehorse waiting for the tape to be raised, it took a great effort not to run off as soon as he left the school grounds. When he got to the pharmacy which had been badly damaged – the character for kusuri or medicine had been shaken off the hoarding above the door and now lay broken on the ground – something jolted inside him, the panic erupted and with it adrenaline pumped to his legs. He ran like he had never run before.

He galloped with blinkers keeping his focus firmly ahead of him, blotting out the scenery which had been so dramatically changed in such a short period of time. He was no longer panicking, rather, acting on instinct and without thinking, motivated purely by the desire to get to where his little sister was.

Some fires burned where gas pipes had been ripped apart when buildings collapsed; sparks from electrical wires ignited this gas that now hissed freely from the copper snakes in which it was once imprisoned. Parts of the road along which he ran were uneven, whole sections of tarmac raised up like miniature geological formations. These were mere hurdles in his race to get to Haruka. The public announcements continued:

Tsunami has been confirmed moving towards the port.

Please move to higher ground immediately.

Tsunami has been confirmed moving towards the port.

Please move to higher ground immediately.

For Shoichi, these words did not register, such was the intensity of his concentration and trace-like state he was in, running towards where he might find his sister. There was nobody around to see Shoichi, they had all evacuated as the warning had implored them to do, nobody around to stop him running closer and closer to the building where Haruka now sheltered on the third floor, closer and closer to where the tsunami was, like Shoichi, single-mindedly tearing across the landscape.

Although the earthquake had taken some buildings its victim, mainly the older corrugated iron warehouses, there were still enough standing in between where Shoichi ran and the port to obscure the view down to the water. He saw the sign to the port office and decided to head that way; if Haruka was not there, at least he would be able to speak to somebody who might know where she and class 4-A had gone.

However, he sensed danger. Like when he had regained consciousness at school, his ears were the keenest of his senses and told him that something was wrong. This was not just water lapping up against the side of the port wall, this was rushing water and his mind went momentarily back to a time standing by a fast mountain river watching water bubble and gurgle around boulders and over fallen trees.

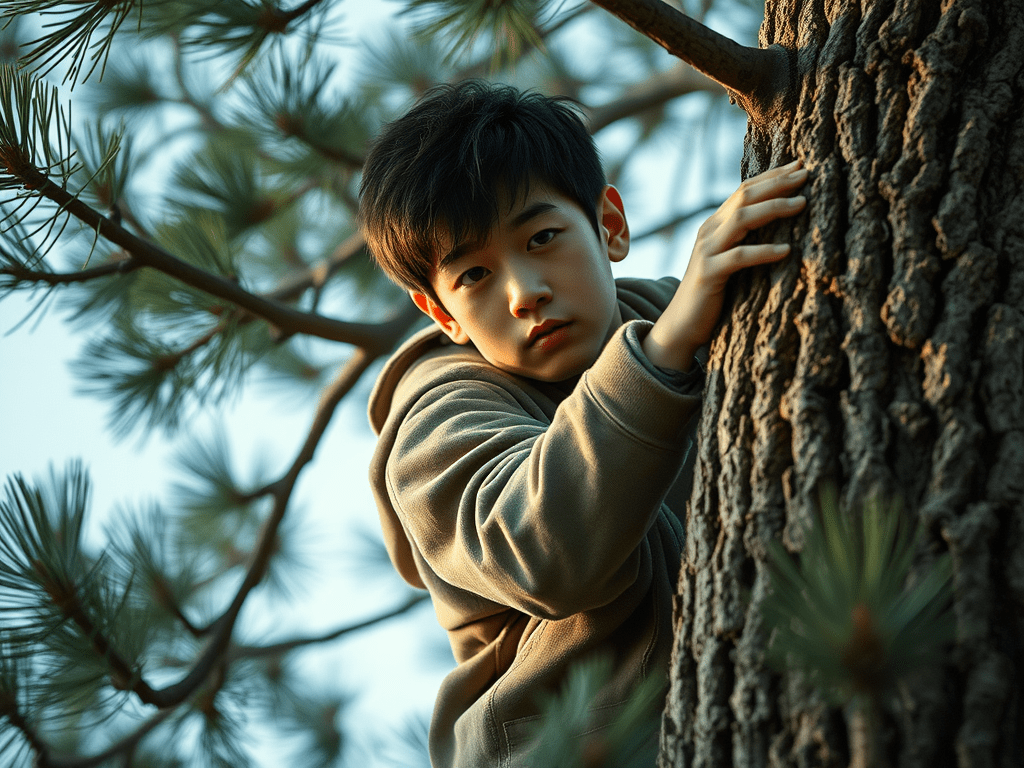

From around the side of the port office and through every gap between every building now standing in front of him, a sinister oily-black pool spread out. He skidded to a halt, and in a fraction of a second had to make a life or death decision: should he turn and run or get as high up as possible to wait this out? Looking at the oncoming water, his brain subconsciously carried out a series of complex calculations at impossible speed and Shoichi realised that this water was moving much faster than he could run. There was no obvious safe place to go until he saw, at the very limit of his peripheral vision, a magnificent pine tree that fortunately for Shoichi had been transplanted from a local forest to become a centre piece in front of a Matsushita Logistics distribution centre twenty- five metres to the right of where he stood.

His legs were elastic, the muscles contracting and elongating in sequence propelling him towards his place of refuge. He leaped up the supporting wooden beams at the base of the tree like a cat and the speed of his run pushed him up towards the lower branches that grew outwards from the trunk. Below him the water that had been blackened by the silt and debris it had picked up along the way swirled around the base of the tree, running into the square concrete surround. The place where he had stood merely seconds before was now completely submerged.

Like on a climbing frame at the park, Shoichi moved arms and legs, fuelled by a further burst of adrenaline, up the natural rungs of the tree pushing and pulling himself towards the top, going as high as he could before the branches eventually ran out. He was about the equivalent of three stories high and hoped that this would be enough. Looking out towards where the water was still rising, Shoichi tried to judge how far up he might expect the tsunami to reach, knowing at the same time that he was helpless to move to another shelter should this one not be tall enough or strong enough to stand up to the force of the water as it continued to move further inland.

From this vantage point, he thought that he spotted something in the water that was thrashing about although the pace of the wave was such that whatever it was had been washed away and out of sight before he was able to take a closer look.